Spring Data JPA is one of the most popular starters used in Spring-based applications. If we look at GitHub statistics, we'll see that developers use Spring Data JPA in more than 900K projects. Compare it with 165K for Spring JDBC, and it becomes obvious that in many tech interviews developers face questions on Spring Data JPA and related technologies.

In this article, we will take a look at the most popular Spring Data JPA interview questions. Also, we'll discuss underlying technologies – JPA and Hibernate. First, there will be some basic questions on general knowledge, and then we'll review advanced topics.

1. Can you explain the difference between JPA and JDBC?

JDBC (Java DataBase Connectivity) – is an API for Java applications that defines how a client may communicate with a database. The API uses abstractions close to the relational database domain: Connection, Statement, ResultSet. It is a low-level database access framework that allows developers to execute SQL statements and fetch results in a table-like format – ResultSet. We can describe its workflow in the following steps:

- Connect to the database;

- Fetch the data from the database in the form of a result set;

- Loop through every record in the result set, create a Java class instance for each record and fill its properties with the record values.

While working with DB using JDBC, we should write a lot of similar boilerplate code to transform records into Java objects. Let's assume that we have a DB table containing records about users: their first and last name and an ID – a unique identifying number. To fetch this data to the application, we should do something like this:

try (Connection connection = DriverManager.getConnection(URL, USER, PASSWORD)) {

Statement statement = connection.createStatement();

ResultSet resultSet = statement.execute(SELECT * FROM user);

List<User> users = new ArrayList<>();

while (resultSet.next()) {

String id = resultSet.getLong("user_id");

String firstName = resultSet.getString("first_name");

String lastName = resultSet.getString("last_name");

users.add(new User(id, firstName, lastName));

}

} catch (SQLException sqlException) {

//...

}

To reduce the amount of boilerplate code, frameworks that automated this routine work using "mappings" from DB tables to Java objects appeared. First, there were text files (usually XML) that specified which class was mapped to which table and which attribute was mapped to which column. Then developers started using annotations right in Java classes to specify these mappings. There is how Object-Relational mapping (ORM) frameworks appeared.

JPA is a specification for ORM frameworks in the Java world. "JPA" stands for Jakarta (formerly Java) Persistence API. This API provides a higher level of abstraction than JDBC. JPA allows us not only to interact with the database but to map records from a database directly to java objects without any manual manipulations from the developer side. The API's essential class is an EntityManager responsible for executing queries and transforming relational data into Java objects. All we need to do is to create a class, map it to a DB table and then pass it as a parameter to the EntityManager along with the query.

Our User class will look like this:

@Entity

@Table(name = "user")

public class User {

@Id

@Column(name = "user_id", nullable = false)

private Long id;

@Column(name = "first_name")

private String firstName;

@Column(name = "last_name")

private String lastName;

//getters and setters are omitted

}

Now, we need to write less code to complete the same task as was shown earlier with JDBC:

entityManager.getTransaction().begin();

TypedQuery<User> query = entityManager.createQuery(

"SELECT u FROM User u",

User.class);

List<User> users = query.getResultList();

entityManager.getTransaction().commit();

entityManager.close();

We also need to mention that not every ORM implements JPA specification. BlazeDS or MyBatis are such examples.

2. What is the difference between JPA and Hibernate?

JPA is a specification. In fact, it is a set of interfaces, and vendors provide actual implementations. Hibernate from RedHat is the most popular implementation in the Java world now. There exist other JPA implementations, e.g., EclipseLink or Apache OpenJPA. Each of them must comply with the JPA specification. Apart from this, some of them usually provide vendor-specific APIs not described in the spec.

3. Name the main JPA objects

In the JPA specification, there are the following main objects:

Entity

– a class that is mapped to a database table. Its fields correspond to the columns of the table. The declaration of a regular JPA entity looks like this:

@Entity

public class User {

@Id

private UUID id;

private String firstName;

private String lastName;

//getters and setters are omitted

}

MappedSuperclass

– a class that declares common attributes for entities. We use this class to build an entity hierarchy to reuse common attributes. Each table associated with an entity from the hierarchy in the database will contain all fields from the MappedSuperclass entity and its descendants. As an example, for the following class hierarchy:

@MappedSuperclass

public class Person {

@Id

private UUID id;

private String firstName;

private String lastName;

//getters and setters are omitted

}

@Entity

public class User extends Person {

private String username;

private String bio;

//getters and setters are omitted

}

We'll need to create a table with columns id, firstname, lastname, username, and bio.

Embeddable

– a class that we can embed into other entities. If we need to treat a pack of fields as one entity and reuse it in various entities, then an embeddable class is what we need. For example, we want to store an address for different entities: user, client, etc. We could use inheritance, but for this case, the composition is preferable:

@Embeddable

public class Address {

public String country;

public String city;

public String street;

public String building;

//getters and setters are omitted

}

@Entity

public class User {

@Id

@Column(name = "id", nullable = false)

private UUID id;

private String firstName;

private String lastName;

@Embedded

private Address address;

//getters and setters are omitted

}

For the User entity, we'll need to create a table with columns id, firstname, lastname, country, city, street, and building. When we fetch the User from this table, we can use their address as a separate object at once.

EntityManager

– a facility that allows us to manage the lifecycle of the JPA entity instance. EntityManager API is a part of the JPA specification. We can create, read, update or delete an entity from a database by using it. EntityManager allows us to execute SQL queries to select entities. Also, we can use a special query language - JPQL – to fetch data. JPQL is similar to SQL but uses classes and attributes in queries instead of tables and columns. Here is an example of EntityManager usage to fetch data:

EntityManagerFactory entityManagerFactory = Persistence.createEntityManagerFactory("default");

EntityManager entityManager = entityManagerFactory.createEntityManager();

entityManager.getTransaction().begin();

TypedQuery<User> query = entityManager.createQuery (

"SELECT u FROM User u WHERE u.address.country='US'",

User.class

);

List<User> users = query.getResultList();

entityManager.getTransaction().commit();

entityManager.close();

Session

– the Hibernate-specific interface that extends the EntityManager. All methods defined by the EntityManager are available in the Hibernate Session. Many other methods in it are unique to Hibernate, e.g., isDirty(), evict(), cancelQuery() and so on...

Then, you may have a reasonable question: "In which cases is it better to use EntityManager, and in which cases is Session"? I will quote Emmanuel Bernard, a data architect on the JBoss Hibernate team. He gives the following answer: "We encourage people to use the EntityManager. From a team point of view, we wish we had only one API. We are trying to push into the standard as much as we can. If we could somehow merge or deprecate the Session in the future, we would do it, but people still use some stuff that is not in the EntityManager, and we don't want to just break everybody's application just for the fun of it."

So, try to use EntityManager whenever it's possible, and when you have no choice but to use Session, unwrap it from the EntityManager:

Session session = entityManager.unwrap(Session.class);

4. Which association types and mappings could you specify?

Like in the relational database model, there are four association types in JPA: one-to-one, one-to-many, many-to-one, and many-to-many. You can define all of them as uni- or bi-directional. It means you can create an attribute in only one of the associated entities or both.

Uni-directional many-to-one association "One User can create Many Posts":

@Entity

public class User {

//id, first name, last name, etc.

//No references to the Post entity. The association is unidirectional.

}

@Entity

public class Post {

//...

@ManyToOne(fetch = FetchType.LAZY)

@JoinColumn(name = "user_id")

private User user; //reference to the User entity

//...

}

Bi-directional one-to-many/many-to-one association "One User can create Many Posts":

@Entity

public class User {

//...

@OneToMany (mappedBy = "user")

private Set<Post> posts = new HashSet<>(); //reference to collection of posts created by the User

//...

}

@Entity

public class Post {

//...

@ManyToOne

@JoinColumn(name = "user_id")

private User user; //reference to the User entity

//...

}

In the relational databases, we have only unidirectional relations (defined as foreign keys). ORM engine gives us more flexibility by providing bi-directional ones. For the latter, we should always keep in mind the limitations of the database side. Thus, when we define a bi-directional association, we should know which side of it is the "owning" one.

An association's "owning" side is responsible for keeping the reference. The corresponding table will have the reference column and foreign key constraint. The "owning" side reference must be populated. Otherwise, the association will not be stored. For the example above, if we add a Post instance to the User.posts collection and save the User entity, the association won't be saved. But if we assign the Post.user field, everything will be OK.

NOTE: To quickly figure out which side is the "owning" one, just look at the annotation on the reference field. If there is the mappedBy attribute – this is the inverse side of the association; otherwise – the owning one.

5. Entity ID, what is it?

According to the JPA specification, Entity is a Java class that meets the following requirements:

- Annotated with @Entity annotation;

- Has no-args constructor;

- Is not final;

- Has an ID field (or fields).

As you can see, ID is required. The reason is simple - ORM engines use the ID to identify each entity instance stored in the database uniquely.

In 99% of cases, IDs are generated. To avoid issues with uniqueness, it is important to choose the right way to generate an ID. We can use a client- or database-generation ID strategy. Which, in its turn, are divided into several more sub-strategies.

When choosing ID type and generation strategy, the rule of thumb is: for the single DB instance, and monolithic application, the server-side ID generation using sequence is the best choice in most cases. If we have microservice architecture and distributed databases, it is better to use UUIDs generated on the client.

In some cases, we can use composite IDs consisting of several attributes. One of these attributes is often a reference to another entity. Composite keys are common, especially when we build an application over the existing database.

The "IDs in JPA" topic is essential and challenging; that's why we can recommend the following articles on it:

- The Ultimate Guide on DB-generated IDs in JPA Entities;

- The Ultimate Guide on Client-Generated IDs in JPA Entities;

- The Ultimate Guide on Composite IDs in JPA Entities.

6. What does the hbm2ddl.auto/ddl-auto property stand for?

In fact, it is a single property, but it has two names. The first one – hibernate.hbm2ddl.auto is used by "pure" Hibernate, while the second one – spring.jpa.hibernate.ddl-auto is a Spring wrapper over the first one. This property instructs ORM on what to do with the database schema. There are five possible values for it:

create– first, Hibernate will drop the database tables mapped to the entities. Then, it will generate and execute a DDL to create a DB schema that complies with the JPA model.create-drop– will do the same as the previous one, but Hibernate will drop the database tables mapped to the entities after the application shuts down.update– Hibernate will generate DDL scripts only for new tables/columns in this mode. Even though the value is calledupdate, it does not create scripts to change or drop existing columns. E.g., if you mark an attribute as unique or drop some from the entity code – Hibernate will ignore it.validate– in this mode, Hibernate will not generate any DDL statements and won't touch your database. It will only check for full compliance of your JPA model with the database. In case of a mismatch, the application will fail to boot with aSchemaManagementException.none– will do nothing.

Indeed, all you need to know about the ddl-auto property is that it's not a good idea to use any of the above values except validate on the production stand. For testing, create/create-drop may be an OK choice. And if you don't want to re-fill the database every time while testing, you can use the update option.

For better development experience, prefer specialized solutions to manage database changes like Liquibase or Flyway. Even simple .sql files written by hand or automatically generated by the JPA Buddy in conjunction with spring.sql.init.mode would do better because you:

- have complete control over the DDL before its execution;

- can set up proper Java to Database types mapping;

- have no issues using the attribute converters and Hibernate types.

You can see it in action in the following video:

7. How to fetch data from the database using JPA?

With JPA, there are several ways to fetch data from the database. Some of them are available out-of-the-box, and some require additional libraries. Let's have a look at them.

NOTE:

We'll code the same thing for each approach to better see the difference. The assignment reads: "You have a PostgreSQL database with one table called "User".

| Column name | Type |

|---|---|

| id | bigint |

| first_name | varchar(50) |

| last_name | varchar(50) |

| varchar(255) |

Write a code to select all users whose email ends with 'gmail.com' and whose name is 'Alice'. Order the result by 'lastName'."

JPQL

This option is available out of the box and is probably the oldest way to fetch data. JPQL is a SQL-like query language created specifically for JPA. EntityManager is responsible for JPQL execution. Here is the task implementation:

entityManager.getTransaction().begin();

TypedQuery<User> query = entityManager.createQuery(

"SELECT u FROM User u " +

"where u.email like '%gmail.com' and u.firstName = ?1 " +

"order by u.lastName",

User.class)

.setParameter(1, "Alice");

List<User> users = query.getResultList();

entityManager.getTransaction().commit();

entityManager.close();

Pros:

- DB-agnostic queries;

- No extra libraries needed.

Cons:

- No query validation at build time;

- Limited capabilities compared to SQL.

Criteria API

Criteria API introduces DSL (Domain Specific Language) to create queries. It allows us to write queries without SQL or JPQL, with Java and string references to entities' properties. As a result, we can build queries not from strings but Java objects. It adds some type-safety when we combine different predicates or add order by clause to the query. Still, a query can fail in runtime due to an entity property name typo. Below is the code for selecting all Alices registered on the gmail.com domain.

entityManager.getTransaction().begin();

CriteriaBuilder cb = entityManager.getCriteriaBuilder();

CriteriaQuery<User> cr = cb.createQuery(User.class);

Root<User> root = cr.from(User.class);

cr.select(root).where(

cb.and(

cb.like(root.get("email"), "%gmail.com"),

cb.equal(root.get("firstName"),

cb.parameter(String.class, "name"))

)

);

cr.orderBy(cb.asc(root.get("lastName")));

TypedQuery<User> query = entityManager.createQuery(cr);

query.setParameter("name", "Alice");

List<User> results = query.getResultList();

entityManager.getTransaction().commit();

entityManager.close();

Pros:

- DB-agnostic queries;

- No extra libraries needed;

- Type safety: we can pass parts of query as a parameter, concatenate them, etc. – fewer chances for typos.

Cons:

- No field names validation at build time;

- The code is hard to read compared to SQL and JPQL.

QueryDSL

QueryDSL is an external library that uses annotation processing to generate additional classes – called Q—types. These are copies of the JPA entities but introduce an API that allows us to create database queries. For example, if you have the User entity with firstName and lastName string attributes, then the generated Q-type will be called QUser and will have attributes with the same name but a different type - StringPath. Each attribute will have specific methods to compose queries. For example, like(), eq(), etc. Those methods form the DSL language that we can use. Let's have a look at the code example:

entityManager.getTransaction().begin();

List<User> users = new JPAQuery<User>(entityManager)

.select(QUser.user)

.from(QUser.user)

.where(QUser.user.email.endsWith("gmail.com")

.and(QUser.user.firstName.eq("Alice")))

.orderBy(QUser.user.lastName.asc())

.fetch();

entityManager.getTransaction().commit();

entityManager.close();

Pros:

- DB-agnostic queries;

- Type safety;

- Compile-time query validation.

Con:

- Require additional dependency;

- Need to regenerate classes on data model change.

Spring Data JPA @Query/Derived methods

Spring Data JPA is a part of the Spring Framework that allows us to use well-designed repositories API to execute database queries using derived method names or JPQL or SQL queries.

Derived methods are repository interface methods named in a special way. They are very convenient for simple queries; sometimes, they may even be more powerful than JPQL queries. For example, there is no way to fetch top N records from the database using JPQL, although, with derived methods, you can complete this task easily.

However, derived methods become hard to read and maintain for massive queries with many conditions. Let's have a look at the interface that can execute the query that we implemented earlier:

public interface UserRepository extends JpaRepository<User, Long> {

List<User> findByFirstNameAndEmailEndsWithOrderByLastNameAsc(String firstName, String email);

}

As we can see, the method name is barely readable. For such cases, we can use pure JPQL or even native SQL. Spring Data framework will do all the heavy lifting on substituting parameters, opening a transaction, etc.:

public interface UserRepository extends JpaRepository<User, Long> {

@Query("select u from User u " +

"where u.firstName = ?1 and u.email like concat('%', ?2) " +

"order by u.lastName")

List<User> findByNameAndEmail(String firstName, String email);

}

Additional bonus – method names and JPQL queries are verified at the application startup. It is not a compile-time check but much better than runtime failure.

Pros:

- No need to learn JPQL and SQL for simple queries;

- Boot-time query validation;

- The code is easy to read and use;

- Adds some extra features like projections.

Con:

- Require Spring Data as a dependency;

- Method names might be cumbersome for complex queries;

- Native SQL queries are not checked at boot-time.

Native Queries

Some SQL clauses are not supported in JPQL and hence in all other JPA-based DSL libraries. For these cases, we can use native SQL in JPA. It gives us some flexibility: we can use carefully optimized queries only when required and use JPA to avoid writing tons of simple SQL queries in other cases.

Here is an example on how to execute SQL in JPA:

entityManager.getTransaction().begin();

Query users = (Query) entityManager.createNativeQuery(

"""

SELECT u.id, u.first_name, u.last_name, u.email

FROM "user" u WHERE u.email like(CONCAT('%', :email)) and u.first_name= :firstName

ORDER BY u.last_name

""", User.class)

.setParameter("email", "gmail.com")

.setParameter("firstName", "Alisa");

List<User> authors = (List<User>) users.getResultList();

entityManager.getTransaction().commit();

entityManager.close();

And here's how it works in Spring Data JPA:

@Query(value = """

SELECT u.id, u.first_name, u.last_name, u.email

FROM "user" u WHERE u.email like(CONCAT('%', :email)) and u.first_name= :firstName

ORDER BY u.last_name

""", nativeQuery = true)

List<User> findByNameAndEmailNative(String firstName, String email);

Pros:

- No limitations – we use pure SQL;

- The code is easy to read and use;

- Simpler to debug queries.

Con:

- Query correctness check only on execution;

- Hard to refactor code on schema change;

- Manual type cast – native queries cannot be properly parametrized.

8. What are the states of an entity in JPA?

JPA specifies four different object states:

- Transient – All new entities have never been associated with an opened database session (Persistence Context) and do not have corresponding rows in the database yet;

- Managed – All entities fetched from the database and associated with a Persistence Context. ORM tracks all the changes made to entities in this state. When we close the session without transaction rollback, ORM automatically submits all changes to the database;

- Detached – Entities transit to this state when the database session is closed. The ORM no longer tracks any changes made to them. To save entities, we need to make them managed again by "attaching" them to the session. The simplest way is to invoke EntityManager's

merge()method. Some frameworks (like Spring Data JPA) can do it automatically. - Removed – entities get into this state after we call the

remove()method. They will only be removed from the database after we flush session changes or close it.

9. Why do we need equals()/hashCode(), and how to implement them correctly for JPA entities?

By default, in Java, object instances are equal if their addresses in memory are equal. For JPA, this approach does not work well. If we fetch the same entity instance in different transactions, their addresses in memory will be different. It might cause problems with caching, issues with Set collections, etc. That's why it is essential to properly define the equals() method for JPA entities.

The same reasoning applies to the hashCode() method implementation. JDK collections framework and Hibernate-specific collections use this method heavily, so the improper implementation may affect application performance, lead to entities "loss" in collections, or even cause runtime exceptions if we use lazy attribute loading. There are some examples of such behavior in the article about Lombok in JPA.

Naturally, entities are mutable. A database often generates even the id of an entity, so it gets changed after the entity is first persisted. This means there are no fields we can rely on to calculate the hash code value or use in entities equality computation. Let's see how we can do it.

By implementing these methods, we should:

- maintain decent performance;

- consider the specifics of the JPA world;

- save the contract between hashCode() and equals().

It looks like the following implementation looks like the most appropriate if we use Hibernate ORM:

@Override

public boolean equals(Object o) {

if (this == o) return true;

if (o == null || Hibernate.getClass(this) != Hibernate.getClass(o))

return false;

User user = (User) o;

return id != null && Objects.equals(id, user.id);

}

@Override

public int hashCode() {

return getClass().hashCode();

}

First, the hashCode() implementation always returns the same value. Even though such an approach is far from the best practices, this option is acceptable and preferable in the JPA world. The reason is simple: all fields, even id, may change when the entity moves from one state to another. So, if we don't want to lose an entity in the collection due to field value change, it's better to have one immutable value.

Such an approach might sound terrible since it defeats the purpose of using multiple buckets in a HashSet or HashMap. However, for performance reasons, you should always limit the number of entities stored in a collection. It would be best if you never fetched thousands of entities to a Set because the performance penalty on the database side will affect your application much more than using a single hashed block.

Accordingly, comparing hash codes in the equals() method makes no sense. The objects in our case will not be equal when:

- the object or its

idis null; - the ids of the objects do not match;

- the objects belong to different classes.

If the objects have the same references, we assume they are equal. Also, when the object IDs match and all checks above pass, we believe that the two objects are equal as well.

10. What does @Transactional annotation do? What are the ways to configure it?

A database transaction is a sequence of actions treated as a single unit of work. In other words, either all actions will be executed or none. Spring provides a powerful mechanism for managing transactions. Simply annotating a method with @Transactional, we automatically open a database transaction when the method execution starts and close the transaction when it finishes.

The questions are: what will happen if we call a transactional method from another one? Should we create a new transaction or reuse the same? If we open a new transaction, should it be able to read data changed in the calling method?

In fact, we can manage transactional methods behavior; let's see how we can do it.

Transaction Propagation

Transaction propagation allows you to specify the behavior if a transactional method is executed when the transaction context already exists. E.g., you can configure it to create a nested transaction inside an already existing one; or suspend an active transaction and create a new one. Here are all the available options:

REQUIRED– the default value. Spring uses the active transaction to execute the business logic. If no transaction exists, it creates a new one.NESTED– If there's no active transaction, it works like REQUIRED. When there is an active transaction, Spring remembers a point where the method was called and creates a new transaction. In case of an execution error, the transaction will be rolled back to the saved point.REQUIRES_NEW– Spring suspends the existing transaction if it exists and then creates a new one.MANDATORY– If there is an active transaction, Spring uses it. Otherwise, it throws theTransactionRequiredException.SUPPORTS– If there is an active transaction, Spring uses it. Otherwise, the code will be executed in the non-transactional form.NOT_SUPPORTED– If there is an active transaction, Spring suspends it. Next, the code will be executed in the non-transactional form.NEVER– Spring throws TransactionalException if there is an active transaction. Otherwise, the code will be executed in the non-transactional form.

Transaction Isolation

Transaction isolation is one of the four ACID properties, along with atomicity, consistency, and durability.

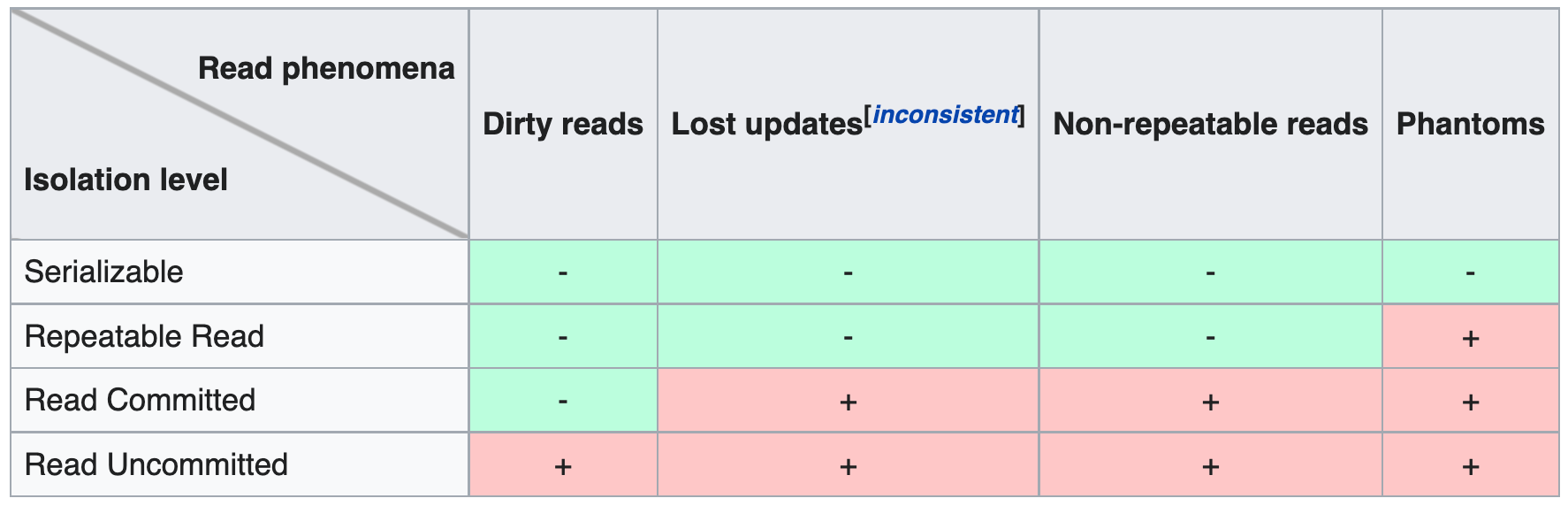

There are four isolation levels:

- Read uncommitted;

- Read committed;

- Repeatable read;

- Serializable.

Each of them determines how users can interact with the data at the same time and what concurrency effects they may get.

Spring fully supports all of them and provides another option – DEFAULT. In this mode, Spring will use the default isolation level of the database.

So, for every transactional method, we can specify an isolation level hence managing changes visibility between transactions.

@Transactional(readOnly = true)

If you only plan to get data from the database and not change it, consider setting the readOnly attribute to true.

@Transactional(readOnly = true)

User findById(Integer id);

You can win some performance points by explicitly telling Spring that you only need to read the data. Also, depending on your database, Spring can omit table locks or even reject write operations you might trigger accidentally.

@Modifying annotation

The @Modifying annotation is designed to be used along with the @Query annotation. When we use these two annotations together, we can perform not only SELECT statements but also INSERT, UPDATE and DELETE ones.

@Transactional

@Modifying

@Query("update User u set u.isActive = true where u.email is not null")

int updateActivityStatus();

Missing @Modifying annotation for the DML (Data Modification Language) query will cause an InvalidDataAccessApiUsage exception at the runtime. To prevent such a mistake, use JPA Buddy. It helps to catch such issues in advance with its smart inspections:

11. Have you ever stumbled upon the LazyInitException? If so, how did you get rid of it?

The LazyInitializationException is probably one of the most common exceptions in the JPA world. Hibernate throws it when you refer to the association that was not loaded from the database, and the entity is detached. Here is a simple example:

entityManager.getTransaction().begin();

TypedQuery<User> query = entityManager.createQuery(

"SELECT u FROM User u",

User.class);

List<User> users = query.getResultList();

entityManager.getTransaction().commit();

entityManager.close();

for (User user : users) {

int size = user.getProfiles().size(); //Here we are stumbling upon LazyInitializationException.

}

Hibernate cannot load the required field from the database when an entity is detached. If we look at the error message, we'll see something like this.

Exception in thread "main" org.hibernate.LazyInitializationException: failed to lazily initialize a collection of role: entities.User.profiles: could not initialize proxy - no Session ...

For lazy loaded attribute values, Hibernate creates proxy classes that use the existing session to load actual values at the first read attempt. Therefore, if the session is closed, the loading fails.

You might think that the most straight-to-the-point way to fix it – execute all the code inside the transaction context. In fact, it is. But in this case, you'll get rid of LazyInitException but get an N+1 problem. So, the right way to fix it - fetch all the required data in one query using a join clause. For example:

entityManager.getTransaction().begin();

TypedQuery<User> query = entityManager.createQuery(

"SELECT u FROM User u join fetch u.profiles",

User.class);

List<User> users = query.getResultList();

entityManager.getTransaction().commit();

entityManager.close();

for (User user : users) {

int size = user.getProfiles().size();

log.info(String.format("User with id=%d has %d profiles", user.getId(), size));

}

Hibernate:

select

u1_0.id,

u1_0.email,

u1_0.first_name,

u1_0.last_activity,

u1_0.last_name,

p1_0.user_id,

p1_0.id,

p1_0.created_at,

p1_0.name

from

"user" u1_0

join

profile p1_0

on u1_0.id=p1_0.user_id

Also, some more advanced options to load required data at once and avoid this exception, such as EntityGraph, DTOs, and Projections.

We can define Entity Graph and specify associations we want to fetch in an annotation @NamedGraph or using Java API. After that, we can pass the graph along with the query, so JPA framework generates a proper query.

DTOs and Projections are used by Spring Data JPA. These are class or interface definitions that contain subset of entity fields. Spring will modify the query based on class definition and fetch specified fields only.

12. What is the N+1 query problem, and how can we fix it?

The N+1 problem occurs when we fetch a list of entities and select associated entities in additional separate queries for every entity in the list. For example, we have the Profile entity that corresponds to the User as many-to-one:

@Entity

public class Profile {

//...

@ManyToOne(fetch = FetchType.LAZY)

@JoinColumn(name = "user_id")

private User user;

//...

Now, let's try to execute the following code:

entityManager.getTransaction().begin();

TypedQuery<Profile> query = entityManager.createQuery(

"SELECT p FROM Profile p",

Profile.class);

List<Profile> profiles = query.getResultList();

for (Profile profile : profiles) {

Long id = profile.getId();

String userEmail = profile.getUser().getEmail(); //Here we will fetch info about email as many times as many users we have in the database

log.info(String.format("Profile with id=%d belongs to user with email: %s", id, userEmail));

}

entityManager.getTransaction().commit();

entityManager.close();

Hibernate executes 1 query to fetch Profiles

select

p1_0.id,

p1_0.created_at,

p1_0.name,

p1_0.user_id

from

profile p1_0

and N additional queries to fetch email for each associated User:

select

u1_0.id,

u1_0.email,

u1_0.first_name,

u1_0.last_activity,

u1_0.last_name

from

"user" u1_0

where

u1_0.id=?

The Profile - User association is lazy, so we load user info only when requested. Since we go through the collection of profiles, we execute a query to load User data N times.

You may think the problem is easy to solve at this point: just change FetchType.Lazy to FetchType.Eager. But this way, you will only worsen it.

Let's test it out. *-To-One associations are of the Eager type by default, so let's simply remove the FetchType.Lazy parameter:

@Entity

public class Profile {

//...

@ManyToOne

@JoinColumn(name = "user_id")

private User user;

//...

Now, let's select all Profiles from the database:

entityManager.getTransaction().begin();

TypedQuery<Profile> query = entityManager.createQuery(

"SELECT p FROM Profile p",

Profile.class);

query.getResultList();

entityManager.getTransaction().commit();

entityManager.close();

We'll get the same queries list executed by Hibernate!

select

p1_0.id,

p1_0.created_at,

p1_0.name,

p1_0.user_id

from

profile p1_0

-- N times

select

u1_0.id,

u1_0.email,

u1_0.first_name,

u1_0.last_activity,

u1_0.last_name

from

"user" u1_0

where

u1_0.id=?

As you can see, this time, we didn't even address any field and have already got the N+1 problem.

To avoid this problem, we should analyze what data we need and try to fetch it using a single query. In the example below, we do it with JPQL, but we also can use EntityGraphs, DTOs, and projections.

entityManager.getTransaction().begin();

TypedQuery<Profile> query = entityManager.createQuery(

"SELECT p FROM Profile p join fetch p.user",

Profile.class);

List<Profile> profiles = query.getResultList();

for (Profile profile : profiles) {

Long id = profile.getId();

String userEmail = profile.getUser().getEmail();

log.info(String.format("Profile with id=%d belongs to user with email: %s", id, userEmail));

}

entityManager.getTransaction().commit();

entityManager.close();

select

p1_0.id,

p1_0.created_at,

p1_0.name,

u1_0.id,

u1_0.email,

u1_0.first_name,

u1_0.last_activity,

u1_0.last_name

from

profile p1_0

join

"user" u1_0

on u1_0.id=p1_0.user_id

13. Apart from JPQL, what are the other ways to select associated entities from the database? (EntityGraph, DTO, Projection)

To avoid the N+1 problem and LazyInitException, we can use the join statement in the JPQL. But there are other options to specify the attributes and associations we want to select. They are:

- Entity graph – specified in JPA standard;

- DTOs and projections – used by Spring Data JPA library.

- Let's have a look at them in detail.

Entity Graph

The entity graph feature has been introduced in JPA 2.1. It has been one of the most awaited features for a long time. Entity Graphs give us another layer of control over data that needs to be fetched. In Spring Data JPA, we can specify the required data right above the @Query declaration. The example below shows how to fetch the User entity along with its profiles attribute:

@EntityGraph(attributePaths = {"profiles"})

List<User> findUserByEmailAndName(String email, String firstName);

Also, we can specify a named entity graph for an entity and reuse it in different places. For example, we can use the graph with the entity manager:

@NamedEntityGraph (name = "user-with-profiles",

attributeNodes = {@NamedAttributeNode("profiles")}

)

@Entity

public class User {

//...

}

//...

EntityGraph entityGraph = entityManager.getEntityGraph("user-with-profiles");

Map<String, Object> properties = new HashMap<>();

properties.put("javax.persistence.fetchgraph", entityGraph);

Post post = entityManager.find(User.class, id, properties);

In Spring Data JPA, it will look like this:

@EntityGraph(value = "user-with-profiles")

List<User> findUserByEmailAndName(String email, String firstName);

DTO and Projection

DTO (data transfer object) is an object that carries data between processes. DTOs for JPA entities generally contain a subset of entity attributes. Spring Data JPA allows us to specify DTOs as a method return type in repositories. Under the hood, Spring Data optimizes the query to fetch only attributes defined in the DTO. We can specify DTO as a class:

public class UserDto implements Serializable {

private final String firstName;

private final String email;

public UserDto(String firstName, String email) {

this.firstName = firstName;

this.email = email;

}

//getters and setters are omitted

}

… or as an interface. Spring Data JPA derives attribute names from the interface's method names. So, for the following definition, it is assumed that the entity has attributes firstName and lastName.

public interface UserDto {

String getFirstName();

String getLastName();

}

The use of DTO does not differ in any way from the repository methods:

List<UserDto> findUserByEmailAndName(String email, String firstName);

As a result, we improve queries efficiency because only specific fields are retrieved from the database. For the repository definition above, the query will be:

select u1_0.first_name, u1_0.last_name from "user" u1_0

14. What are L1 and L2 Caches in Hibernate?

Establishing a connection to the database and obtaining the necessary data is usually the most time-consuming process. If it is possible to save previously selected data and return it when the same request is received, you can significantly improve the application's performance. This is precisely what L1 and L2 caches do.

Let's start with the L1 cache, also known as persistence context. It is a session-level in-memory cache. The L1 cache is an integral part of the Hibernate and caches entities during the session. All entities in the L1 cache are in the attached state. Since L1 cannot be disabled, keeping the session open for a long time is not recommended to avoid extensive memory consumption and to keep data up-to-date.

Let's assume that we have a blog application. One user can write many posts and many comments. Each post can have many tags, and one tag can mark many posts. If we open a transaction and fetch a list of comments, Hibernate will store comments data in the L1 cache along with associated users. The reason is that Hibernate loads all *-to-one associations eagerly by default. Then if we start getting posts for users, then tags for posts, Hibernate will keep loading entities into L1. So, if we don't close the transaction, we can accidentally load the whole database into memory "just" by navigating through the entity graph.

For the same blog application, we can get another issue if we keep long transactions. Let's assume that we have a post "JPA with Hibernate" with ID = 1 tagged with the "Java" tag. And there is the following code in our application (executed in one transaction):

List<Post> posts = postRepository.findByTags_Name("Java");

Post post = posts.stream().filter(p -> p.getId() == 1).findFirst().orElseThrow();

//Someone updated post text in another transaction

Post postById = postRepository.findById(1L).orElseThrow();

The issue is that for the last statement Hibernate won't even execute SQL, it will fetch data from the L1 cache. Therefore, we won't see changes until we close the transaction and execute the query again.

In contrast, the L2 cache is not connected to a Hibernate session and can share stored data between sessions. L2 cache is disabled by default. Thus, when we have L1 cache only, and two users request the same data from the database, Hibernate will execute two identical queries. With the L2 cache enabled, only one database call will be executed. Hibernate looks for the data in the L1 cache, then in the L2 cache, and only then executes the database query. Let's enable the L2 cache and have a look at the following non-transactional test method:

@Test

void testL2CacheQueries() { //The method is not under @Transaction

Post postById = postRepository.findById(1L).orElseThrow();

postById.setTitle("New title");

postRepository.save(postById);

Post postById2 = postRepository.findById(1L).orElseThrow();

assertEquals(postById.getTitle(), postById2.getTitle());

}

You'll see that Hibernate executes only two queries:

select --column list

from post post0_

left outer join user_1 user1_ on post0_.user_id=user1_.id

where post0_.id=?

update post

set title=?, user_id=?

where id=?

The test will pass because the L2 cache is designed to be strongly consistent. So, it can help us to improve the application performance even for read-write transactions. The only drawback – is if we use native SQL queries, the whole cache can be invalidated. To prevent this, we need to explicitly define entities that we update.

15. Why and how to test Spring Data repositories?

A repository is an object that mediates between the domain and the data mapping layers. So, repository testing means that it should:

- Generate proper queries that select data we need;

- Generate the exact number of queries.

There is not much sense to test spring data repositories as separate units, in isolated context using mock instead of a database. The main purpose of repositories is to execute queries against a real database, so we talk about integration testing.

For this kind of testing, we need to set up a database with a pre-defined data set and then test how repositories work. Application tests should use fixed data, so in theory we need to recreate database for each test suite to avoid test interference.

To simplify database setup, it is recommended to use testcontainers library. The beauty of this library is that it allows us to run the database of the same vendor that we use in production, if it can run in a container. With testcontainers we can easily run a database instance for every test, test suit or for all tests, whichever way we prefer.

Apart from the database instance, we need to create database schema and fill it with test data.

There are several ways to create database schema:

- Let Hibernate generate and execute DDL automatically;

- Use DB versioning scripts (Flyway or Liquibase);

- Create

schema.sqlDDL manually and run it using Spring Boot settings.

The first option is OK as a starting point, but it is pretty limited. For example, Hibernate does not take into attribute converters and type mappings. Also, we cannot control the generated DDL.

The second option works fine, but brings a bit too much overhead. We need to go through all DB evolutions for each test over and over again. Other than that, we can use it pretty safely, but tests execution may take much time.

The third option looks like a preferred solution for unit testing. We have one script that represents the final database state and takes into account all application-specific type mappings, converters, indexes, etc. The only drawback – we should update it every time we update our data model.

To fill the database with test data, there are three main options:

- Insert data in the test code;

- Use

@Sqlannotation for tests; - Use

data.sqlfile and run it using Spring Boot settings.

The first option is good if you have a very small test dataset, literally a couple of tables and a couple of records for each table. When the database grows, we need to update tons of code: copy common data, keep track of references etc.

The @Sql annotation is great to run SQL scripts to fill the database with test-specific data. For every test we can create small maintainable scripts, and we can see their names right above the test methods. That's convenient.

As for the data.sql file – we can use it together with schema.sql. It can be used to fill the database with common reference data like countries, cities, etc.

So, for Spring Data JPA repositories testing, the perfect solution looks like this:

- Use testcontainers and the same database as running in production;

- Initialize test database schema using

schema.sqlfile; - Initialize common reference data using

data.sqlfile;

For single tests, use @Sql annotation to create data for this exact test

Also, there is a nice tutorial on creating integration tests with testcontainers, intelliJ IDEA and JPA Buddy on YouTube:

16. What is Lombok library? How is it useful for JPA, and how can it harm?

Lombok is a library targeted to replacing boilerplate code writing with annotations and bytecode instrumentation. For example, we don't need to write getters and setters, all we need to do is to annotate class with @Getter and @Setter and these methods will be generated automatically in runtime.

It looks like an ideal library to clean up JPA entities code, but to use lombok right, we need to deeply understand which exactly methods are generated and what is inside. Classic example: generated equals() and hashCode() methods may cause LazyInitException. By default, they use all fields, including associations. Associations in their turn, may be lazily initialized. When we add detached entities into a collection, the collection class invokes the equals() method under the hood... so, we get the exception. For attached entities, we get an extra query that loads associated entities. Anyway, it is definitely what we expect from the method invocation. To avoid it, we should explicitly exclude associations from those methods by annotating correspondent fileds by @ToString.Exclude.

There are more examples of pitfalls when using lombok in the JPA Buddy blog.

17. What is better for *-to-many associations: List<> or Set<>?

In JPA, efficiency is not about data structures being used for entities, but about queries. Both List and Set can cause N+1 problem, that can be resolved by using JPQL, entity graph, or projections in Spring Data JPA. In contrast to List, Set cannot contain duplicate elements. It means that we need to define equals() and hashCode() methods for the child entity, which is good practice anyway.

List is more common in JPA world, but we need to remember one thing. Let's have a look at the following entity and related repository which selects an owner with all their pets:

@Entity

public class Owner {

//id, name

@OneToMany(mappedBy = "owner", cascade = CascadeType.ALL, orphanRemoval = true)

private List<Dog> dogs = new ArrayList<>();

@OneToMany(mappedBy = "owner", cascade = CascadeType.ALL, orphanRemoval = true)

private List<Cat> cats = new ArrayList<>();

//setters, getters

}

public interface OwnerRepository extends JpaRepository<Owner, Long> {

@EntityGraph(attributePaths = {"dogs", "cats"})

List<Owner> findByNameLikeIgnoreCase(String name);

}

If we use two one-to-many associations with List collection and try to fetch both eagerly, we will get MultipleBagFetchException on the application start. The reason why Hibernate throws this exception is that duplicates can occur with two associations. The List is implemented by the PersistentBag in Hibernate and the latter cannot deal with duplicates.

In this case, replacing Lists to Sets can help, but there is a big drawback – we will get cartesian product in the query. It can greatly impact the query performance. We'll get the following SQL

select

...

from

owner owner0_

left outer join

dog dogs1_

on owner0_.id=dogs1_.owner_id

left outer join

cat cats2_

on owner0_.id=cats2_.owner_id

where

upper(owner0_.name) like upper(?) escape ?

To fix this for good, we need to split data fetching into two queries and fetch the owner two times with two collections separately in one transaction as recommended in this article. The L1 cache will help us to merge the second collection into the existing Owner entities.

public interface OwnerRepository extends JpaRepository<Owner, Long> {

@EntityGraph(attributePaths = {"cats"})

List<Owner> findWithCatsByNameLikeIgnoreCase(String name);

@EntityGraph(attributePaths = {"dogs"})

List<Owner> findWithDogsByNameLikeIgnoreCase(String name);

@Transactional

default List<Owner> findByNameLikeIgnoreCase (String name) {

List<Owner> ownersWithCats = findWithCatsByNameLikeIgnoreCase(name);

List<Owner> ownersWithDogs = findWithDogsByNameLikeIgnoreCase(name);

return ownersWithDogs; //or cats, they are the same in L1 cache

}

}

18. What are the pros and cons of using "open session in view" mode in Spring apps?

The spring.jpa.open-in-view setting in Spring Boot applications binds a JPA Entity manager to the current web request. In means that the application keeps the database session open while we process the request. In Spring Boot 2.x it is enabled by default. And this behavior has its pros and cons.

Pros:

- We won't get the

LazyInitExceptionwhile we create a very complex JSON for our REST API or tricky model for the MVC page; - That's it.

Cons:

- Long database sessions affect its throughput hence the app performance;

- We do not control additional queries, so we can get N+1 query problem;

- All additional queries open transactions in

auto-commitmode, every statement flushed transaction logs, so we impact DB performance again.

Using Spring Data JPA, Hibernate or EclipseLink and code in IntelliJ IDEA? Make sure you are ultimately productive with the JPA Buddy plugin!

It will always give you a valuable hint and even generate the desired piece of code for you: JPA entities and Spring Data repositories, Liquibase changelogs and Flyway migrations, DTOs and MapStruct mappers and even more!

All the above means that disabling this mode would be good practice. Spring Boot developers implicitly warn us about problems by showing the following message on the app start: spring.jpa.open-in-view is enabled by default. Therefore, database queries may be performed during view rendering. Explicitly configure spring.jpa.open-in-view to disable this warning.